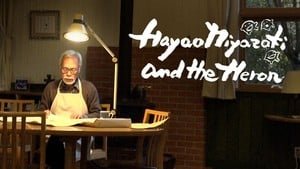

| Having previously directed Never-Ending Man: Hayao Miyazaki and 10 Years with Hayao Miyazaki, Hayao Miyazaki and the Heron (henceforth Heron) is far from the first time director Kaku Arakawa has gotten up close and personal with the legendary anime director. But it’s arguably the first time he—or anyone else, for that matter—has documented Miyazaki at such a profoundly low point.Taking place largely during the long seven years that The Boy and the Heron was in production, Heron follows Miyazaki throughout the process of its development and creation. It focuses on the many trials and tribulations Miyazaki endured, whether artistic, personal, existential, or otherwise. For those wondering whether or not it’s necessary to have seen The Boy and the Heron before watching this: frankly, you’ll be able to appreciate Heron much more if you’ve already seen it, yes. It’ll give you better context for the specific moments/aspects of the film that we see Miyazaki working on, and by extension, giving extra meaning and weight to those moments. That being said, there aren’t massive spoilers for The Boy and the Heron, so while it’s not very in the spirit of the famously un-marketed film, it’s also not the end of the world if you decide to watch Heron first.If there can be said to be one foremost theme in this documentary, it’s mortality. At 82 years old (at the time of The Boy and the Heron’s premiere), Miyazaki is starting to outlive an increasingly long list of his colleagues. Of particular focus in this documentary includes his longtime friend and rival Isao Takahata (whom Miyazaki calls Pak/Paku), who passed away in 2018. Miyazaki, who gave a eulogy at Ghibli’s farewell ceremony for Takahata, struggled greatly in the aftermath of Takahata’s death. The reverberations were felt throughout Miyazaki’s experience working on The Boy and the Heron.If you haven’t already picked up on it, this documentary can often be very depressing. Some moments that range from bittersweet to heartwarming are peppered throughout, and they’re sandwiched by things like deaths or Miyazaki feeling frustrated with his illustrations. The further you get into the documentary, the more it becomes clear that while it certainly played a role, the pandemic was far from the only thing that kept The Boy and the Heron in production for so remarkably long.Speaking of, it feels almost inevitable that a documentary spanning seven years might have pacing issues—though going into the documentary, I was more worried about too many things happening too quickly. But surprisingly, at times Heron has the opposite issue: at some points, it starts to drag on for what feels like ages. To a certain extent, this was probably intentional—to help the audience better feel just how painfully long things were taking. And if that’s the case, mission accomplished; there were multiple points throughout the two-hour documentary where I couldn’t believe it had only been five minutes since the last time I checked where I was. This issue probably could’ve been resolved, or at least downplayed, if this were a docuseries (probably four half-hour-long episodes), which I think—if all the episodes weren’t just dumped all at once—could still help to give the audience a different version of the feeling of time passing slowly. This was probably strategic and intentional to some extent.Even during Heron‘s slowest moments, it was nonetheless interesting to get such a rare glance into The Boy and the Heron’s making-of and to hear from Miyazaki himself about certain scenes, aspects, and decisions. Adding another layer of dimension to Heron is that while Miyazaki is its protagonist, the audience is occasionally reminded of things like his workaholic tendencies and how frustrating his perfectionism can be to those around him—and usually, this is discussed by Studio Ghibli co-founder Toshio Suzuki. By the end, it’s hard to feel like you don’t have a more well-rounded—and certainly much more human—understanding of Miyazaki as both a creative and a person.The view we get of both Miyazaki and The Boy and the Heron through Heron is a unique and fascinating one, making it something I’d recommend to fans of The Boy and the Heron—well, to Miyazaki/Ghibli fans in general, but especially to those who enjoyed The Boy and the Heron—and want a full understanding of everything that went into it. However, Heron is the rare case where I could also see it having some appeal even to people who didn’t particularly enjoy The Boy and the Heron, provided they at least have some level of interest in Miyazaki (either as a person or a creative). This is a documentary about the production woes of The Boy and the Heron. Since he spearheaded the film, you can’t talk about those woes without also talking about the more human woes of Miyazaki because, as we see throughout Heron, the two are often wholly tangled with one another. |